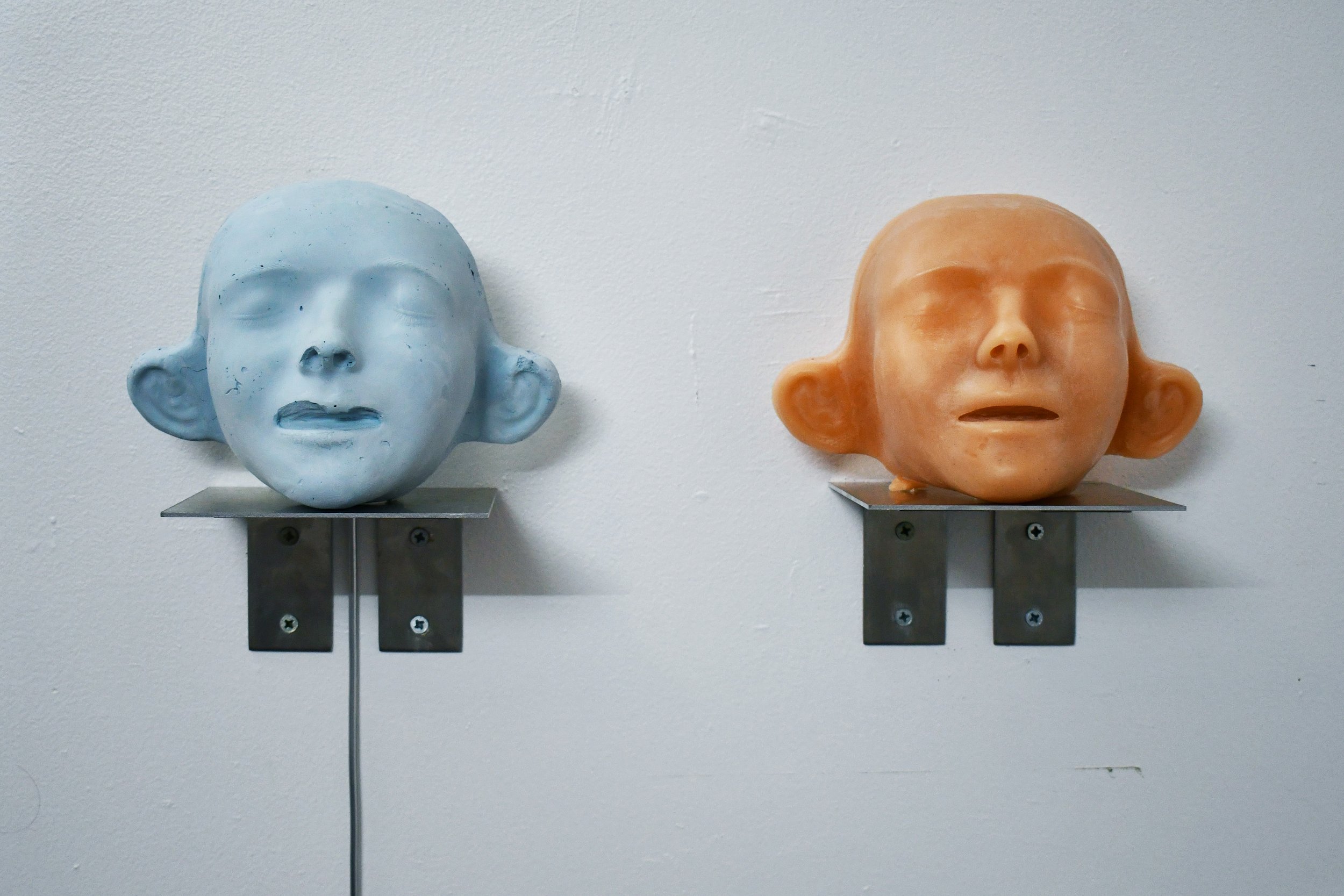

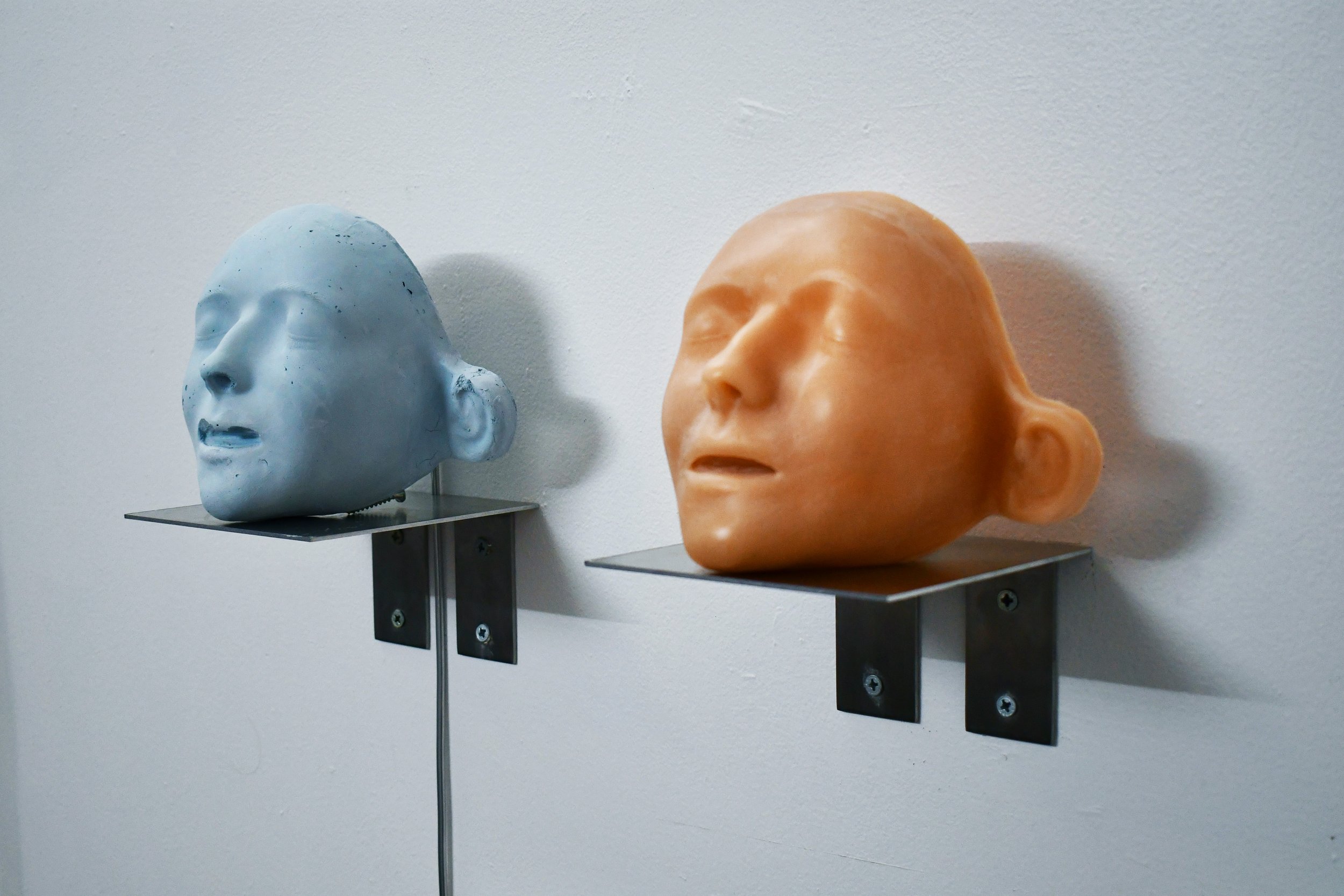

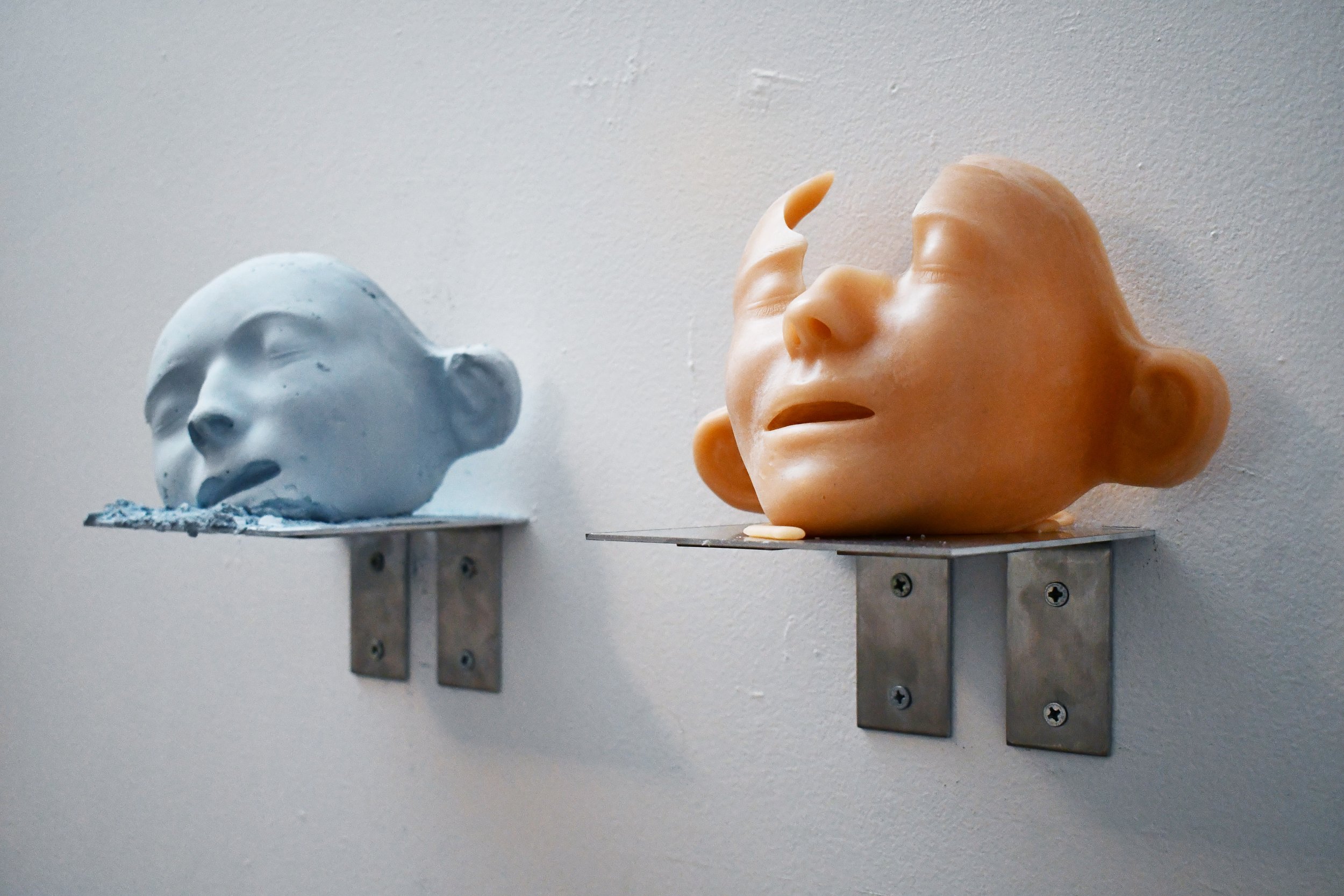

Overpressed Spirits

Doused, Ignited

2022

In this piece, clay and wax casts of CPR manikin Resusci-Anne’s face are decayed over time via water and fire. A metaphoric and elemental re-enactment of L’Inconnue de la Seine’s apparent death and recovery as Resusci-Anne, ‘recovery’ is not what it seems. This is an experimental, exploratory piece, coming out of a body of historical research into the philosophical and technological origins of resuscitation. See below for more context.

The title refers to a line in Shakespeare’s Pericles, which Britain’s first resuscitation organization, the ‘Royal Human Society for the Apparently Dead',’ would quote in defense of their activities to the Church - “Death May Usurp on Nature many Hours, And yet Fire of Life Kindle Again, the Overpressed Spirits.”

9 x 4 x 6.5” each

Porcelain clay, plaster, paraffin wax, vybar, pigment, candle, water, fire, steel shelves, aluminum tube, aluminum tray, water pump

1880s Paris: industrialization is changing the economic and environmental landscape, resuscitation techniques have been in use for about a century, and an unknown teenage girl is found drowned in the Seine (1). Her countenance was so lovely and strangely peaceful that the mortician responsible for her body made a death mask of her face… so goes the story of L’Inconnue de la Seine. While the origins of her iconography are shrouded in myth, what’s happened since is more or less a matter of record, though no less surreal. Her death mask came to populate fashionable salons all over Western Europe, and her character influenced the work of Rainer Maria Rilke, Man Ray, and Vladimir Nabokov, among many others. Her likeness became so ubiquitous that it purportedly influenced women’s beauty fashions until the 1930s. In 1960, Asmund Laerdal manufactured the first ever CPR manikin and modeled its face after L’Inconnue’s; he called it ‘Resusci-Anne (2).’ Her likeness is still produced, and is available in wall sculpture and bust forms, in variable sizes, all over the internet (3). Laerdal Medical still manufactures and sells Resusci-Anne manikins (4).

The allure of L’Inconnue’s pale, mute, inert feminine image touches on its era’s intermingling of life and death - the romanticization of young tuberculosis victims and Victorian deathly pallor, the ‘science’ of spiritualism, headless department store mannequins and ecstatic anatomical manikins with splayed guts (5). Later, her double Resusci-Anne, “the most kissed face of all time,” breathes life back into her in the name of medical advancement - she is eternally saved, forever savable, immortal. She epitomizes the mythos of the innocent white girl as victim - both deserving of resuscitation, and capable of saving others. The moral drama of resuscitation belies the underlying fears and fallacies of this fairy tale of death’s reversal - in spite of a mountain of scientific research and medical advancement, resuscitation is hardly more successful at returning patients to their former lives than it was in L’Inconnue’s time (6). Even so, the entire medical establishment, and the general public, continue to put their faith in science as a cultural strategy for dealing with sudden death in a society that won’t face it’s finality. The repercussions of this worldview extend beyond the strictly medical, touching ecological and social crises that too often come to a head in the emergency room. Racial and class disparities (brought about in large part by capitalist industrialization and its colonial projects) in who is exposed to unsafe living and working conditions, who is able to access medical care, and how they are treated when their lives are on the line, within and beyond the hospital, lead towards difficult questions as we stand on the brink of ecological collapse - who’s death is considered an unacceptable, avoidable tragedy? And who’s is an acceptable, unavoidable loss (7)? L’Inconnue/ Resusci-Anne, the idealized victim, speaks through 150ish years of Western ‘progress,’ from both sides of the grave, to give insight into the dominant cultures’ ‘standard operating procedure,’ and its severe impacts.

1. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Paris during and after the French Revolution (1789 to mid-19th century). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Paris/Paris-during-and-after-the-French-Revolution-1789-to-mid-19th-century.

Timmermans, S. (1999). The Search for the Best Resuscitation Technique. In Sudden death and the myth of CPR (pp. 31–55). essay, Temple University Press.

2. Grange, J. (2013, October 16). Resusci Anne and L'inconnue: The Mona Lisa of the Seine. BBC News. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24534069.

3. Google. (n.d.). Google Shopping: L'Inconnue de la Seine. Google shopping. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://bit.ly/3saRkvg

4. Laerdal Medical. (n.d.). Resusci Anne QCPR - high-performance CPR skills for First Responders. Laerdal Medical. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://laerdal.com/ca/products/simulation-training/resuscitation-training/resusci-anne-qcpr/.

5. Warner, M. (2003). Ethereal body: The quest for ectoplasm. CABINET. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/12/warner.php.

Hetrick, B. (2006). Mannequins, Mass-Consumption and modernity in au bonheur des dames : The Department Store as Ladies' Paradise? . Equinoxes - A Graduate Journal of French and Francophone Studies, (7). Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://www.brown.edu/Research/Equinoxes/journal/Issue%207/eqx7_hetrick.htm.

Lawlor, C. (2013). The British Society for Literature and Science. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from http://www.bsls.ac.uk/reviews/romantic-and-victorian/katherine-byrne-tuberculosis-and-the-victorian-literary-imagination/.

Macdonald, F. (2016, May 26). Why These Anatomical Models Are Not Disgusting. BBC Culture. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160526-why-these-anatomical-models-are-not-disgusting.

6. Timmermans, S. (1999). CPR for All. In Sudden death and the myth of CPR (pp. 56–89). essay, Temple University Press.

7. Roediger, D. R. (2020, July 20). Historical Foundations of Race. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race.